Beyond the Crystal Ball: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Interpreting Climate Models

In the world of corporate strategy, climate models are no longer a niche interest for scientists. They are a topic of discussion related to operational resilience and risk planning. As frameworks like the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and regulations like California’s SB 261 gain momentum, finance and operations teams are increasingly tasked with running climate scenario assessments.

But for many, these models feel like a "black box." How are they built? Why should we trust them? And most importantly, how do we turn a spreadsheet of technical data into a board-ready strategy?

How Climate Models Work: The Mechanics of a Digital Earth

At their core, climate models (or Earth System Models) are massive simulations of physics. They have evolved from simple atmospheric models developed decades ago into complex, interdisciplinary systems that couple the atmosphere, oceans, land, and ice.

The Global "Mesh"

To simulate the entire planet, scientists create a three-dimensional grid or "mesh" over the Earth’s surface. Each cell in this mesh contains data points where flow and energy equations (like the Navier-Stokes equations) are solved.

Resolution Matters: In areas where the atmosphere is denser or human assets are more concentrated, models often use higher resolution to capture finer details.

Computational Power: These models are so large that they require supercomputers and data centers to run. A typical simulation might advance through 100 years of climate data in one-hour time steps.

Externalities and Forcing Conditions

Climate models don’t "solve" for human behavior; they react to it. Scientists impose "forcing conditions"—primarily greenhouse gas emissions—into the model to see how the climate responds. These assumptions are organized into scenarios that help us visualize different possible futures.

The Gold Standard: Why Climate Models are Trustworthy

Speculation about the accuracy of climate modeling is common, but the industry relies on a rigorous, international ecosystem of peer-reviewed science.

The CMIP Ecosystem

The most important acronym in climate modeling is CMIP (the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project). CMIP projects represent an ensemble of climate models that simulate the physics and chemistry of our planet to predict future climate conditions. CMIP contributions are made by international government and research organizations, such as NASA, UK Met Office, Max Planck Institute in Germany, University of Tokyo, and dozens more. The output of CMIP models are raw climate data such as project temperature extremes, precipitation shifts, sea-level rise, and more. Now in its sixth iteration (CMIP6), this global effort brings together the latest science from reputable organizations to model climate, assess uncertainty, and improve accuracy.

CMIP takes the climate models of these international organizations and creates ensembles. By using ensembles—running many different models and comparing the results—scientists can identify a "consensus" path. For businesses, these data can serve as the foundation for operational resilience and robust risk management with respect to climate events. Beehive utilizes CMIP6 data as its baseline, ensuring that our risk assessments are built on the same gold-standard data used by the international scientific community.

Verification Against History

While no model is a perfect crystal ball, they are constantly validated against historical data. By running models "backwards" to see if they can accurately simulate the last 50 years of climate history, scientists can fine-tune the physics for future projections.

Interpreting the Scenarios: SSPs and RCPs

When you interact with the Beehive platform, you often encounter options for different SSPs (Shared Socioeconomic Pathways). These represent different "what-if" stories for the world:

SSP1 (The Orderly Pathway): A world where governments move quickly toward clean energy and sustainable policy.

SSP3 (The Disorderly Transition): A more fragmented world with slower technological progress.

SSP5 (The High-Stress Scenario): A "worst-case" scenario driven by high fossil fuel usage and rapid economic growth without decarbonization.

Business Tip: Most corporates report across multiple SSPs. While SSP1 (a low-emissions scenario) is the goal, assessing your assets under SSP5 (a high-emissions scenario) acts as a "stress test." If your business is resilient under the harshest conditions, you are well-prepared for any pathway.

Translating Science into Business Decisions

The biggest challenge in climate modeling is the gap between scientific timeframes and business timeframes. Scientists often look toward the year 2100; businesses rarely look beyond five or ten years.

Relative vs. Absolute Risk

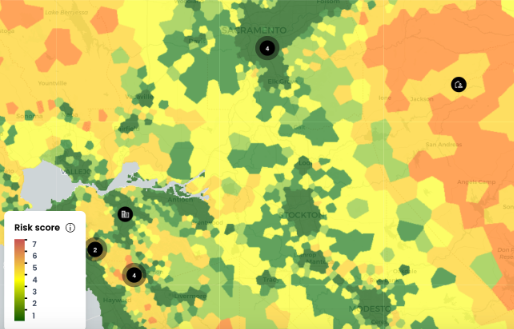

In the Beehive platform, we translate complex climate variables into a 1-to-7 risk score. The scores generally represent a gauge of how robust the risk is compared to global benchmarking. Different climate hazards carry different percentile rankings for the risk scores; thus, they are generally communicated as “Low”, “Medium”, or “High” (as outlined below) in order to be more easily digestible within an organization.

Scores 1–3 (Low): Below average relative risk compared to global benchmarks. Not likely to impact organization operations in the short term, but helpful context for long term strategic planning.

Scores 4–5 (Medium): Roughly average relative risk compared to global benchmarks. It is important to be aware of these risks in the short team, and necessary to understand and digest for long term strategic planning.

Scores 6–7 (High): Above average relative risk compared to global benchmarks. Companies should actively plan operational resilience in the short term and strategically/financially plan for these risks in the long term..

Beehive’s intuitive UI makes it easy to digest this risk and foster discussions within your organization.

Beehive’s Physical Risk Mapping showing the 30-year wildfire risk over Sacramento

For the more specific risk scoring percentile rankings for each climate hazard, reference Beehive’s documentation.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Modeling

The field of climate science is active and evolving. We are currently looking toward CMIP7, which promises even higher resolution and better physics models.

Furthermore, AI and Machine Learning are beginning to transform the space. By using AI to "fill in" high-resolution details in traditional models, we can generate more localized insights at a lower energy cost. As these technologies mature, Beehive will continue to integrate the most reliable advancements into our platform.

Summary

Climate models are not meant to be perfect predictions; they are tools for managing uncertainty. By understanding the science of the mesh, the consensus of the CMIP ecosystem, and the practical application of SSP scenarios, your business can move from reactive reporting to proactive resilience.

To hear more on this topic, watch our previous webinar with input from Dr. Edward Knudsen as he delved into more detail on how climate models work and impact our organization: